Open Payments: The Cinderella Story of Finding a Fitting Authorization Method

Written by Nathan LieThe Internet Runs on OAuth 2.0

If you’ve ever signed into a website with your Google account, Apple ID, or perhaps an account on a social media website, then you’ve participated in a grand tradition of access delegation that began back in 2007, when the core protocol for the first iteration of OAuth was released. Since then, the protocol has expanded into what we see throughout the web today in the form of OAuth 2.0.

At a certain point in Rafiki’s development it became necessary to implement a standard that described how third parties could initiate payments on behalf of someone else. This standard came to be known as Open Payments, which not only would have to provide a framework to describe those payments, but also incorporate an access delegation method for those third parties to use. Having such a well-established access delegation method like OAuth 2.0 made it seem like a clear choice as an authorization method for this standard.

However, as Open Payment’s methods for describing and managing payments became fleshed out, the shortcomings of OAuth 2.0 for that use case revealed themselves. To understand what they are, let’s first go over the features of OAuth 2.0 that helped propel it into mainstream popularity.

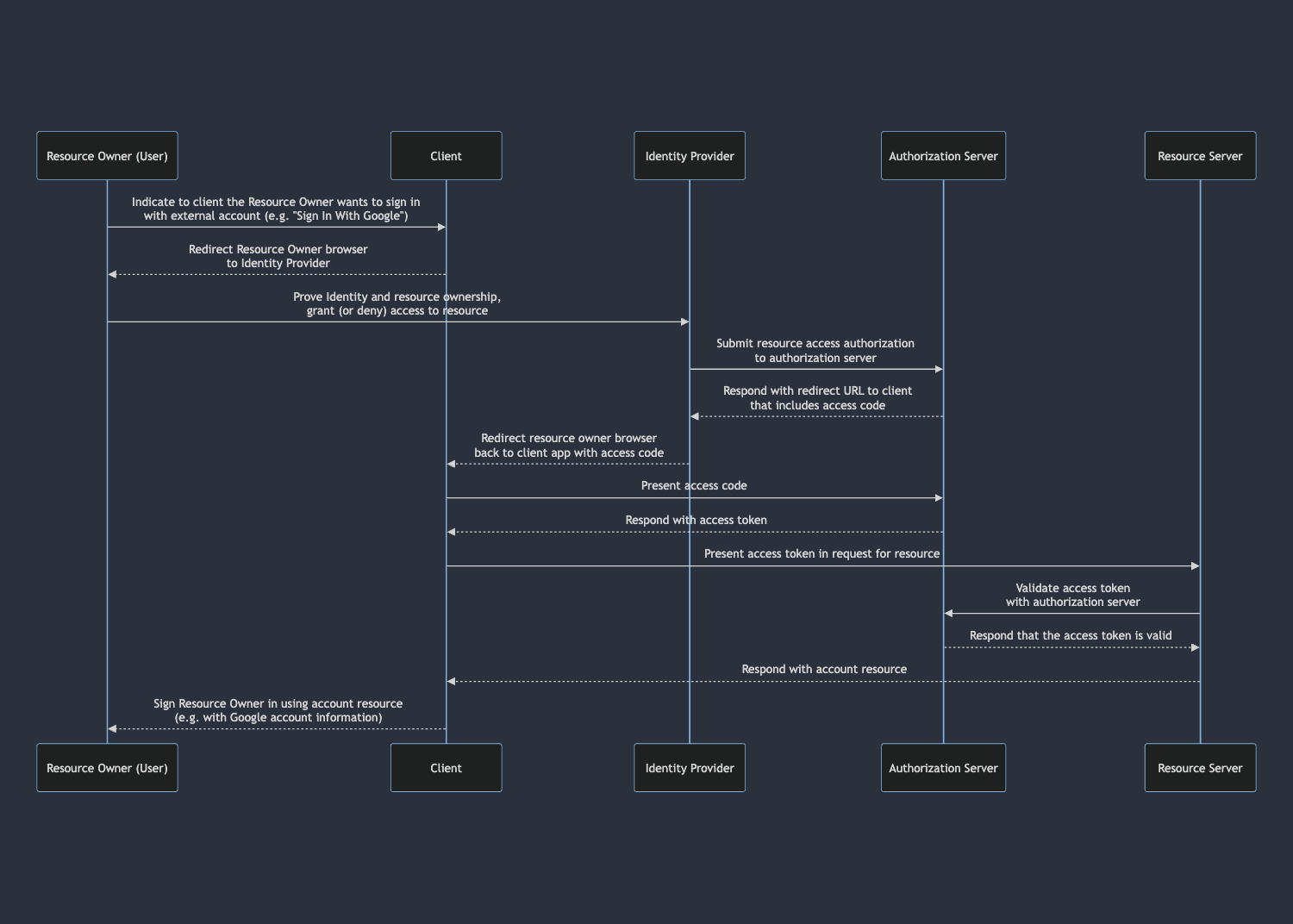

As simple of a process as it is for a user, access delegation through OAuth 2.0 is achieved through a lot of moving parts by different parties. These roles are as follows:

- Third Party Client (or just client)

- The party that is requesting access to a resource that it does not own.

- In a “Sign in with Google”-type example, this is the party that is sending the user to Google to give the client access to information on the user’s Google account.

- Resource Owner

- The entity that owns one or more resources that may be accessible through an authorization flow.

- In the “Sign in with Google” example, this would be the user that owns the Google account.

- Resource Server

- The place where a resource owner’s resources (e.g. an account’s email address or username) are stored.

- In the “Sign in with Google” example, this would be the Google server where the account is stored.

- Identity Provider

- The entity that determines the identity of the resource owner, so that they may access their resources.

- In the “Sign in with Google” example, this would be the Google login page the resource owner is directed to when selecting the option to sign in with Google on the client site.

- The party that controls this often has overlap with the party that controls the resource server, but not always. Note how in the “Sign in with Google” example Google owns both the login page and the resource server that account resources are stored on.

- Authorization Server

- The server that delegates access to the resources on a given resource server.

- The client makes a request to the authorization server to receive an access token for resources owned by a resource owner on a given resource server.

- The resource server makes requests to the authorization server to ensure access tokens presented by a client are valid for the resource the client is requesting access for.

- In the “Sign in with Google” example, this would be a Google server that manages authorization. The authorization server isn’t always run by the same entity as the resource server, and may be outsourced.

When the client needs to perform an action using a resource hosted externally (like signing into their app with a user’s Google account), the client requests access by making a request to the corresponding authorization server for that resource. The authorization server responds with a redirect URL that goes to an identity provider used by the resource server. This redirect also contains information that identifies the client and specifies what resources it wants access to.

The client then redirects the user to a page on the identity provider with that URL. Typically this page will verify the user’s identity by requiring them to provide login credentials in some fashion, then present them with a consent screen asking if they would like to approve or deny the client’s request for access.

Once the user completes the flow on the identity provider, the authorization server gives the client a token which is used to communicate with an API on the resource server to retrieve the resource in question.

Let’s collect this all into a nice sequence diagram.

While extremely useful, OAuth 2.0 is best suited for delegating access to information. Sadly, when one is interested in delegating control, rather than access, the tradition of OAuth 2.0 begins to fall short. A typical OAuth 2.0 authorization is initialized when a third party client generates a link for a resource owner that contains, among other things, a “scope” value that contains a list of the items the authorization should grant access to. For example:

scope = 'email,username,channels:read'In this example lifted from Slack’s OAuth API, this scope will grant access to a resource owner’s email address and username. In addition, it will allow the channels of a Slack instance to be read by the third party client.

Now, the issue with expressing access only as a string, is that it’s cumbersome to express any specifics on the access that’s being granted. Slack attempts to solve this by concatenating parts together, but for a payment, there are enough parts where it becomes really clumsy. Imagine what the scope for a payment might look like with this model, accounting for things like the transaction amount and a billing frequency of once a month:

scope = 'outgoing-payment:100:USD:P1M'This approach is starting to push the boundaries of convenience and ability to parse the scope. Do we need to enforce an order in which information is added to a scope, so that it can be parsed properly? How would we handle optional parts? Should we just stringify a JSON object and call that a scope? From a development standpoint, things are starting to get out of hand.

Trying to Make it Work with OAuth 2.0

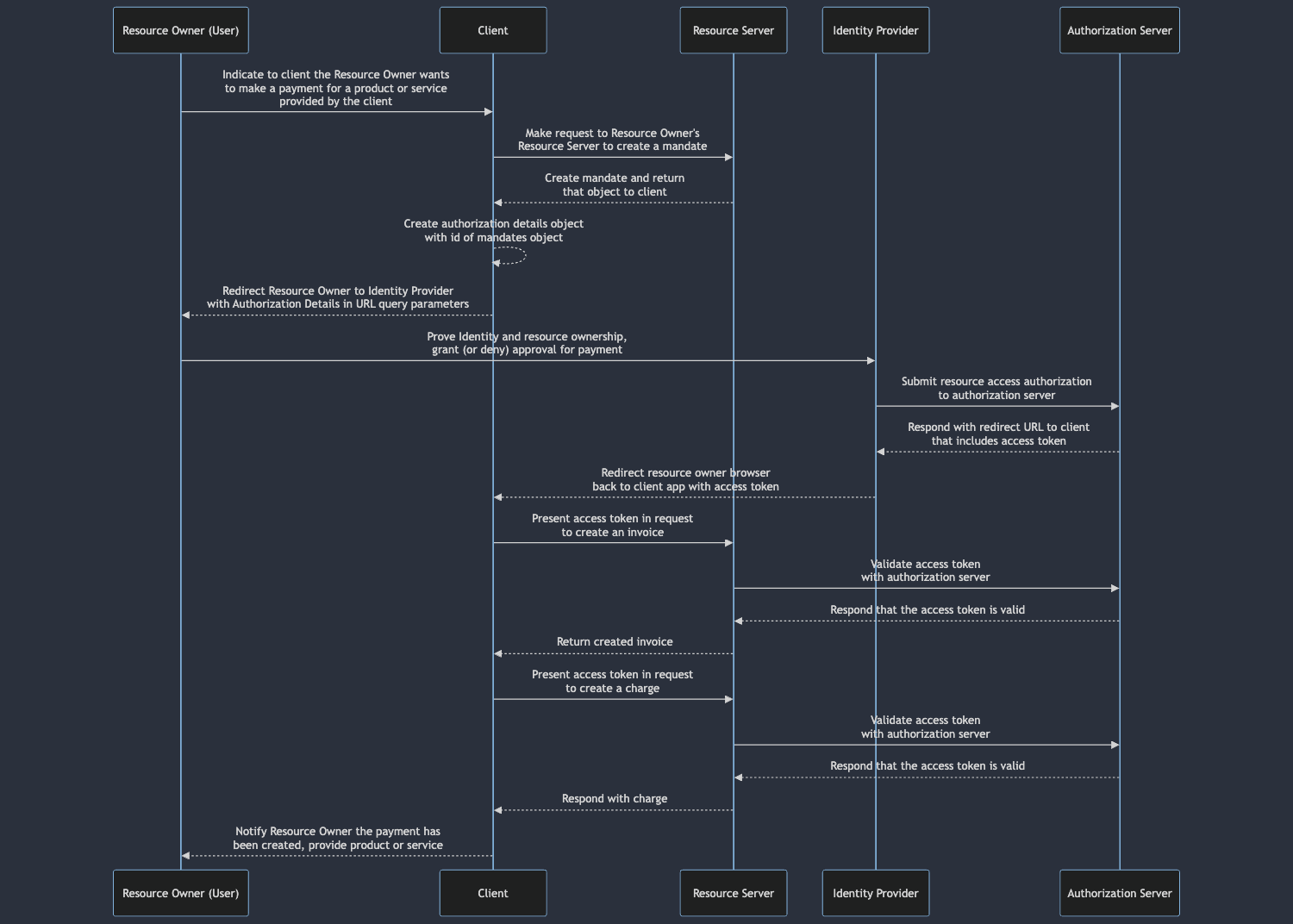

An early attempt to add this context to an authorized payment was through something called “mandates”. These were objects that a third party client would create on an Open Payments resource server that contained the aforementioned payment information. That mandate would then be referenced inside of a Authorization Details object, which would then be stringified and passed as a query parameter in an OAuth authorization URL:

GET /authorize?response_type=code&client_id=s6BhdRkqt3&state=af0ifjsldkj &redirect_uri=https%3A%2F%2Fclient%2Eexample%2Ecom%2Fcb &authorization_details=%7B%0A%20%20%22open_payments%22%3A%7B%0A%20%20%20%20%20%22mandate%22%3A%7B%0A%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%22name%22%3A%20%22%2F%2Fissuer.wallet%2Fmandates%2F2fad69d0-7997-4543-8346-69b418c479a6%22%0A%20%20%20%20%20%7D%0A%20%20%7D%0A%7D HTTP/1.1Host: wallet.example

// URL contains stringified copy of the following object:// {// "id": "https://wallet.example/mandates/2fad69d0-7997-4543-8346-69b418c479a6",// "account": "https://wallet.example/bob",// "amount": 200,// "assetCode" : "USD",// "assetScale": 2,// "interval": "P1M",// "startAt": "2020-01-22T00:00:00Z",// "balance": 200// }Now we’re getting messy again. It’s immediately clear how much noise is in the “authorization_details” query parameter, and in a more practical sense, there’s the added step of creating the mandate before a client can request authorization from a resource owner. We haven’t even gotten into the fact that a whole other object, a “charge”, needs to be created on the resource server in order to make use of the mandate. It’s additional overhead for the resource server to maintain all of those mandates for a process that ideally should be handled entirely by the authorization server delegating access.

Compare this sequence diagram with the previous sequence diagram and the increased complexity. There’s more interaction with the resource server just to set up the authorization flow and more work after the flow in order to initiate the payment.

A New Approach

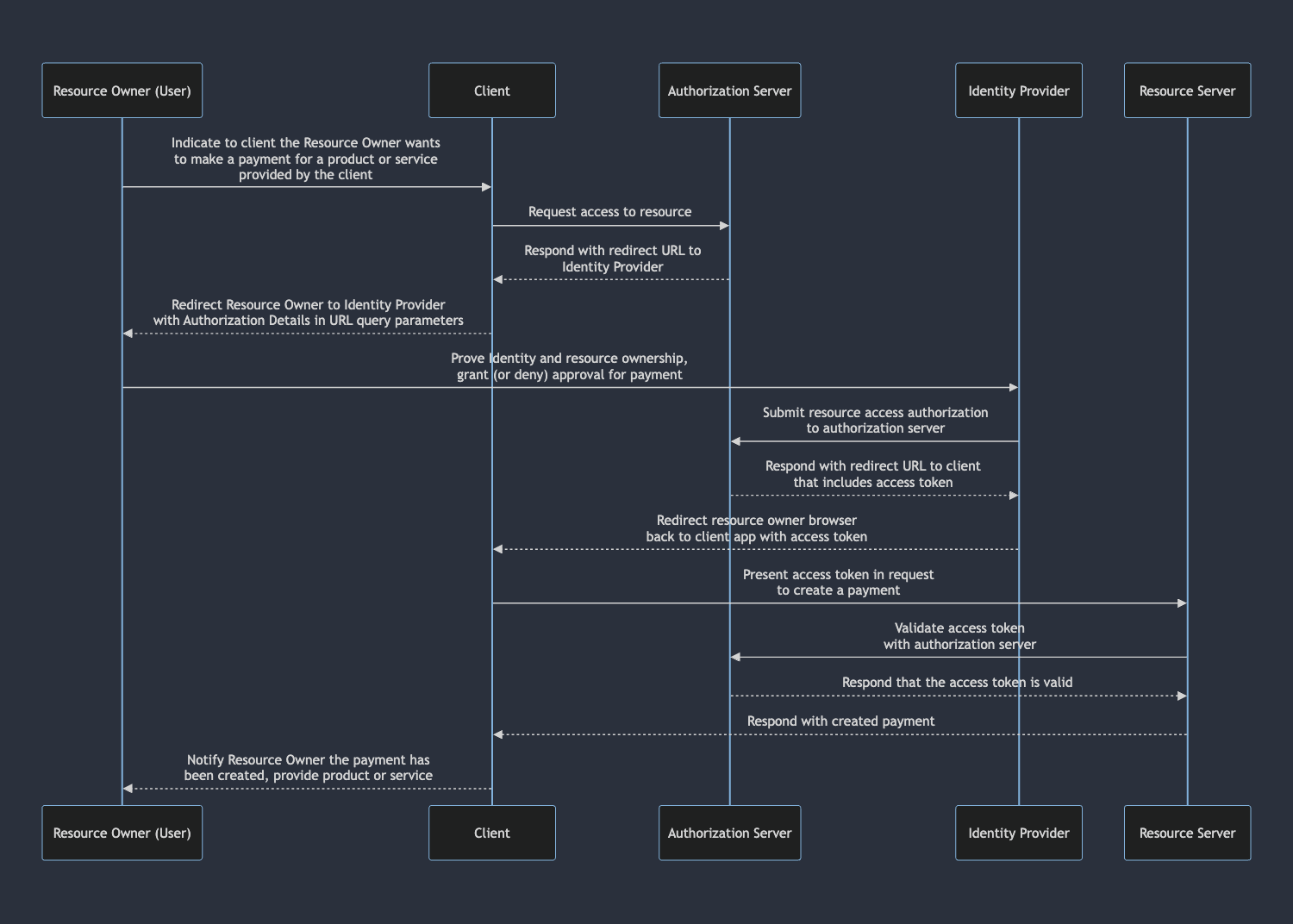

Enter the Grant Negotiation and Authorization Protocol (GNAP), the heir apparent to the OAuth lineage. While maintaining the standard of security that OAuth established, GNAP is capable of authorizing a broader range of actions. Consider the authorization of a payment. Not only does the ability to make a payment need to be specified when authorizing it, but also the recipient and the amount of the payment. Those complications are difficult to account for in OAuth, but much easier to handle in GNAP.

Like mandates, a client will make a request to the Open Payments Auth Server specifying what permissions it would like to have on a resource. The difference here is that this request is part of the spec, so it doesn’t have to live on and be maintained by the server. Additionally, it’s capable of expressing the limitations and caveats on the permissions it’s requesting that we need to properly describe a payment. GNAP achieves this through the grant request. This example describes how a client making this request can create or read outgoing payments for a particular incoming payment for 5 dollars:

{ "access_token": { "access": [ { "type": "outgoing-payment", "actions": ["create", "read"], "identifier": "https://ilp.rafiki.money/alice", "limits": { "receiver": "https://ilp.rafiki.money/incoming-payments/45a0d0ee-26dc-4c66-89e0-01fbf93156f7", "interval": "R12/2019-08-24T14:15:22Z/P1M", "debitAmount": { "value": "500", "assetCode": "USD", "assetScale": 2 } } } ] }, "client": "https://webmonize.com/.well-known/pay", "interact": { "start": ["redirect"], "finish": { "method": "redirect", "uri": "https://webmonize.com/return/876FGRD8VC", "nonce": "4edb2194-dbdf-46bb-9397-d5fd57b7c8a7" } }}After the grant request is made, the Open Payments authorization server responds with a URL that kicks off an authorization flow, similar to when a client makes a request to an OAuth 2.0 authorization server. There are many components to the grant request, but the most important to describing a payment is the “access” field:

"access": [ { "type": "outgoing-payment", "actions": [ "create", "read" ], "identifier": "https://ilp.rafiki.money/alice", "limits": { "receiver": "https://ilp.rafiki.money/incoming-payments/45a0d0ee-26dc-4c66-89e0-01fbf93156f7", "interval": "R12/2019-08-24T14:15:22Z/P1M", "debitAmount": { "value": "500", "assetCode": "USD", "assetScale": 2 } } }]Note how much more specific and readable a grant request can be with its intentions for a payment. The “actions” field can hold what actions can be performed on the resource. Importantly, the “limits” field is open-ended enough that it can specify the amount of the payment, the currency it is in, and its frequency (if applicable) in an understandable way. Essentially, it is able to use two important features of OAuth 2.0 and the “mandates” system without creating significant overhead:

All access delegation is kept within an authorization server, making accounting the resource server’s sole responsibility. There is a clear way to describe the parameters for a payment.

For reference, we have a more tame sequence diagram with GNAP. It’s closer to the baseline set by the OAuth 2.0 sequence diagram and keeps the responsibilities of the resource server properly separated from the authorization flow at large.

With this in mind, it’s clear that GNAP is best suited for sending payments via Open Payments. Though the spec is not officially final, progress is steady and the future looks promising - the specifications are well on their way to becoming a proper RFC. The core protocol was recently approved by the IESG and has entered the IESG editor’s queue. The specification for resource servers is also on the cusp of being submitted to the IESG for publication.

For more information on Open Payments as a whole, consider perusing the documentation.

As we are open source, you can easily check our work on GitHub. If the work mentioned here inspired you, we welcome your contributions. You can join our community slack or participate in the next community call, which takes place each second Wednesday of the month.

If you want to stay updated with all open opportunities and news from the Interledger Foundation, you can subscribe to our newsletter.